I like the term walking simulators. I think it’s funny. You know what game simulates physical walking really well? Firewatch. Firewatch pulls the tricks from The Last Of Us that make Joel feel like a two-ton bag of rocks, especially when he falls. The walking simulation in Firewatch is strong. Which is good, because it’s one of the only physically frictive systems in the game.

What is Firewatch?

Firewatch is a 2016 video game for the XBOX ONE, Playstation 4, Mac, Windows and Linux. It is developer Campo Santo’s first game, and was published by Campo Santo and Panic.

In Firewatch, you play Henry, who takes a summer 1989 fire lookout job in the Shoshone National Forest. Hank brings some baggage with him, but he strikes up a friendship with his supervisor Delilah, who is holed up in a tower like Hanks some seven miles away. Over the course of Firewatch, you do a little fire watching, but mostly you talk to Delilah. Sometimes you hike, read, take photos, listen to wildlife or just let your real-life human eyes unfocus a bit and take in all the beautiful colors. Firewatch has astounding colors.

Firewatch is brief, and utterly engaging.

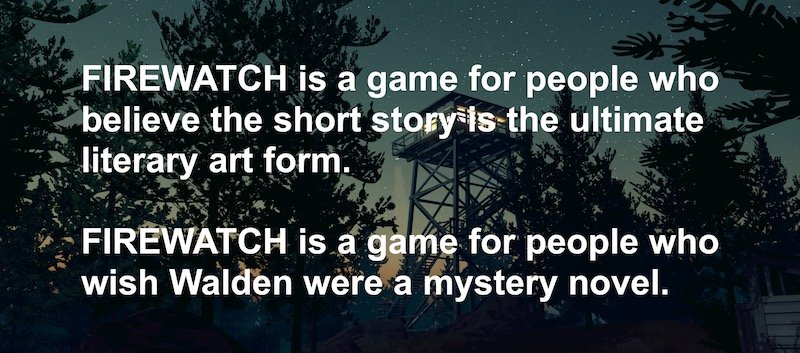

Firewatch is a game for people who believe the short story is the ultimate literary art form.

Firewatch is a game for people who wish Walden were a mystery novel.

What is the word “frictive”?

I might have made it up, but I know what it means. Frictive means causing or relating to friction.

What is friction (in video games)?

You know when you’re playing Mario and he runs right across the screen but when you lift your finger from the right arrow on the D-pad he slides a little bit, like he actually weighs something? Like he has inertia? That’s friction. It’s like your fingers over sandpaper or your wood-soled dress shoes over a freshly polished floor.

Check out Tim Rogers on this, if you’re curious why it’s important that in Firewatch your feet definitely weigh more than your torso.

There’s other physical friction in Firewatch. Player-character Henry’s interactions with objects are animated with satisfying stickiness, but they’re largely divorced from player input. PRESS SQUARE to chop down a tree, but you won’t really feel the chunk of the axe.

The most important friction in Firewatch isn’t physical but narrative, though it’s a game system in of itself. Firewatch belongs to the long (if recent) video game tradition of pairing two characters and making them chafe until they spark.

Friction is resistance formed when one surface slides against another. When those surfaces are people, you get the oldest conceit in storytelling history. Video games aren’t new to this trend. After all, they’ve been causing person-to-person friction since you (with 80% health) stole the pizza your sister (30% health) desperately needed in Teenage Mutant Ninjas 2: The Arcade Game (1989).

But developers have become interested in developing stories by isolating two people. Usually, this is less Vladimir and Estragon and more Bert and Ernie. Get them to rub each other the wrong way to reveal the extent of their underlying affection.

At its best, character friction results in tightly scripted, emotionally harrowing drama that works ludically and narratively, as in The Last Of Us (2013). Equally strong: the comic call-and-non-response of Portal (2007). At its worst, you get something like Leon and Ashley’s soppy friction in Resident Evil 4 (2005), a game that’s an otherwise astounding accomplishment.

(Too often, this friction has part and parcel to the “dadification of games,” a term that popped up everywhere around the release of The Last Of Us and Bioshock Infinite (2013). There’s a lot of interesting scholarship in this. Especially if the word patriarchy doesn’t make you blanche or snort.)

Firewatch, more than any other game in recent memory, really nails character friction. For a game primarily set in a Walden-like arcadia, Firewatch is seldom meditative. For much of its four-hour playtime, Firewatch is an exceptionally tense game. Not DOOM bullet-hell tense, not sliver-of-health-bar Street Fighter intense. It’s frictions result from escalating and de-escalating dialogue options.

Remember that moment in the original Mass Effect (2009) when the television reporter asks you a question you don’t like and should you choose to respond angrily, instead of responding your player-character just steps forward and clocks the reporter in the face? There’s no warning, no indicator that should you choose that dialogue option your player-character will instead silently K.O. an otherwise innocent woman. It’s an astounding moment and bad bit of design.

Firewatch is the exact opposite of this.

Or, rather, Firewatch learns all the lessons of that brilliant gaffe.

Firewatch features a lot of dialogue trees. Its conversations are almost exclusively between the player character, Henry, and his supervisor, Delilah, over a two-way walkie talkie radio. Because you cannot see Delilah and she is a voice on the radio, and because the story increasingly raises the personal and external stakes of your conversations, there is a legitimate tension to every choice. You are left to wonder, “Will saying this inadvertently sucker punch Delilah? Or me?” This is an astounding feat in games, because it’s just like real life.

Real Life (circa 2017) features a lot of dialogue trees. Almost whenever you are speaking to someone, they are an unknowable entity full of fathomless depths. Delilah and Henry are as real as two characters in video games are likely to get right now. They’re each a fascinating D&D character sheet of personality traits, as the game literally makes clear at one particular plot point, but they subvert and grow beyond these traits as well. They’re real and round. They’re thick and meaty as Henry’s fingers. They have the whorl and precise ambiguity of a fingerprint. I really, really liked spending time with them. Their friction was fantastic.

A phrase or a word can create sparks. Sometimes, my reactions to Delilah pissed her off. Sometimes, they pissed me (and by extension Henry) off. Almost always I felt like talking to her. In a few solitary moments, I didn’t. Delilah isn’t the impressive, animalistic AI of the Alien in Alien: Isolation (2014), she a written human, a series of systems. But in this regard, she ranks among some very good other written systems — the kinds you find in books. But because of the branching dialogue trees, there’s an element of inertia to your conversations. Step too far, gain too much momentum, and you might not be able to turn around.

It’s a calculated, fascinating use of friction. It’s something we’ve seen experimented with in Telltale’s various episodic series, most notably The Walking Dead: Season 1 (2012), which several members of Firewatch developer Campo Santo worked on. But rarely has it been so careful, so subtle and so engrossing. Perhaps this is the benefit of working with a small cast, with an area of isolation. After all, previous video games working off the two-character dynamic like The Last Of Us or Bioshock Infinite didn’t isolate its protagonists so much literally as figuratively, in a hail of bullets, blood and constant violence. In Firewatch there’s a paucity of systems. This allows the devs to focus on the depth of the dialogue tree, but it also provides fewer distractions. And with fewer guns, fewer killings, something closer to reality — for better or for worse.

Firewatch gets to the frictive systems at the heart of everyday life. ★